- Home

- E. E. Knight

Baltic Gambit Page 2

Baltic Gambit Read online

Page 2

She worked her way around to the west entrance, cradling her old, seemingly gnarled sword-stick. The two men at the door looked solemnly alert. A broad patio almost encircled the round part of the hotel. Soldiers were standing and smoking. Perhaps she could try there.

Sliding from patch of growth to pile of broken tile to heap of cleared growth—they had spruced up the hotel for the conference, it seemed—she drew close enough to distinguish the facial hair on the guards.

Fading back into the hillside, step by careful step she headed for the lower lands south of the hotel. The wide road running up to the parking entrance divided the hotel from a rather overgrown garden and some kind of outbuildings that had trees growing out the broken windows. The garden smelled like sweet rot, and she instantly identified the smell of death.

She crossed the road with an easy stride, hoping that she would be seen only at a distance and mistaken for someone with business at the hotel, then quickly took shelter beneath a picturesque bench ringing an oak. None of the men on the porch gave any indication that they’d seen her; their eyes were light-blinded.

A crunching step approached. Heavy boots with the measured tread of a cop walking his beat. Her back burned with the fear of a Reaper, but she glanced up and saw a mustachioed face. A Reaper could no more grow a beard than achieve an erection. Probably a southerner, then. Ordnance soldiers were almost all clean-shaven.

He glanced at the men on the balcony, unzipped, and urinated on a tree root extending from beneath the bench. He whistled a non-tune as he did so, sounding more like he was trying to entertain a bird than form music. She kept her face buried in the soil, feeling the warm splatter strike her hair.

She heard a sharp intake of breath. She looked up and saw the surprise and embarrassment in his eyes.

“It’s all right,” she said. “Warmest I’ve been all night.”

Rolling and lashing up, she caught him with the handle of her sword-stick in the solar plexus. His breath came out with a whoosh as muscles involuntarily contracted. So much for a scream for help.

Not wanting blood, she rose and struck again, this time across the back of his neck. That put him on the ground, giving her a moment to unloop the nylon cord around her wrist, slide its falsely decorative beads out of the way, and finish him quietly by strangulation.

Sorry, sport, she thought. Shit luck for both of us.

She heard laughter from the balcony.

Some of her clan relished swapping stories of Kurian atrocities. They tried to convince one another that their victims deserved their fate, that justice was being done. She held to no such illusions. The moment he saw her it was her life or his, and she intended to keep on living—at least through the death of another Kurian or two.

If she just left the body there, it would be a fine starting point for trackers.

With an effort, she lifted him into a fireman’s carry and tottered across the road, as far outside the paired decorative streetlamps as she could manage. She staggered to the hedges surrounding the outbuilding.

She followed her nose to the death smell. It was strong… and she was approaching it from upwind.

She burst through a hedge and almost fell into a long trench. The bottom was lined with bled-out bodies, mostly older specimens. She saw a half-closed stomach scar on one younger specimen—the victim of a botched operation, it seemed. All the bodies near her except the one with the cut above the appendix bore the distinctive tongue marks of a Reaper at the base of the neck or in the upper rib cage.

“Holy mother—,” she began, then clamped her hand over her mouth and nose.

She set the body down as quietly as she could.

A growl sounded from the hedge line behind her. She froze, searched out of the corner of her eye.

A dog and a handler stood thirty feet away, peering into the darkness. The dog was alert to her, but the handler couldn’t see her in the night shadow.

She flowed down into the body pit at the speed of molasses running on a hot day. The dog whined and pulled.

The bodies were soft and rotting.

The handler raised a flashlight and cast the beam of light carefully into the darkness where she’d been squatting a moment before. She pulled her sword-stick tight into the crook of her arm and covered it with the withered leg of an old man. He had bristly hair.

The beam of light passed over her, resting on her breast for just a moment. In the glare, her own healthy flesh wouldn’t be markedly different from the flesh of the bodies.

The dog padded forward, leading the man holding its leash. It sniffed about and snorted in disgust.

The body of the guard she’d dropped drew the handler, following the beam of his flashlight, which had caught the Ordnance insignia, a sort of elongated pentagon—a stylized capital “O.”

Slithering with sword-stick cradled, she approached across the bodies. The corpses made noises like sponges.

The handler drew something shiny from his pocket, attached to a short lanyard. A whistle. Its sound could carry a mile or more.

She sprang upward, drawing her blade from the stick. “Help me!”

Arms out and open as though pleading, or rushing to embrace him, she ran forward.

He was having none of it. He put the whistle to his lips—

But no air would enter it. She’d opened his throat at the center of his Adam’s apple, the blade slicing as neatly through the nylon cord of the whistle’s lanyard as it did the cartilage and tissue of his neck.

He toppled, a confused look frozen on his face.

“Hssssss!” she hissed at the dog. It ran toward the outbuildings, dragging its leash.

Even better, she thought grimly as she hid the bodies under layers of Reaper waste. One dead or missing man would inspire a careful search. Two would be enough of a mystery that the search would concentrate on the missing men rather than a wiry, scuffed-up redhead.

She retrieved her pack from her cache on the hillside and put as much timber and earth as she could between herself and the Kurians.

She dug a shallow pit with her folding camp shovel and surrounded it with the flattest rocks she could take from a watercourse. She set her sole tin pot atop it and started boiling the beans she’d been soaking. It wasn’t an ideal stove, but just as practical as a campfire, and you could see the flicker of flame only by standing over it.

With a little wild mushroom, her beans, honey, and a piece of bacon for flavor it made a decent stew.

A familiar soft step crept up on her campsite.

“You didn’t see the fire, did you?” she asked.

“Smelled your stew,” said Clay, the Wolf who’d crossed the Hoosier forest with her two days ago. “Why aren’t you camping at our rendezvous?”

“I did check it—through my optics. You must have been away. I didn’t remain. Left you a note in the drop that I’d check back for you or another note. If a Reaper grabbed you and started removing digits, there might be a little welcoming party at the spot.”

“The idea doesn’t seem to bother you that much,” Clay said. Poor kid. He’d been a little squirrely ever since they woke snuggled up to each other against the night’s spring chill. He’d brushed her breast, pretending it was an accident. When she didn’t respond, he didn’t press the matter, thank heaven.

Silly. She didn’t do recreational sex, not on a job, not with a comrade. She’d fucked and sucked her way into a few headquarters and pass-only Quisling “Green Zones,” but that was business, not distraction.

The Wolf was just a kid. But then, most of them looked like kids to her these days. God, she wasn’t even that old, just into her thirties.

She liked Wolves. They used their eyes, ears, and noses, and fought only when they had no choice, or a strong advantage. They could run all day on a few mouthfuls of porridge.

Wolves listened to reason. Bears did whatever the fuck would lead to the most blood.

She let the kid finish and light his pipe. He looked like a boy playing with his father’s toba

cco stand. The pipe had a long plastic stem and the bowl was a rather elegantly carved animal face that she supposed was meant to be a fox; the snout was way too narrow and the ears too wide to be a wolf. The tobacco was rather noxious cheap Kurian Zone ration compared to the rich, aromatic Carolina import that Colonel Lambert, the leader of Southern Command forces in the Kentucky Theater, smoked.

They chatted about what the weather promised over the next few days, and then she broke the news.

“You’ll have to run again, I’m afraid, and find Brigade HQ. The hotel is worth hitting with everything we can put onto it.”

His eyes flared. Eagerness? The Wolf’s buckskin leathers meant he had nothing to prove, at least not to anyone who’d seen his breed cover thirty miles in a day, running and shooting all the way. “Why didn’t you tell me earlier?” Clay said.

“If you’re going to be running all night, I thought it best that you do it on a full stomach.”

“I didn’t have to kill an hour smoking… .”

“Maybe you didn’t, but your digestion did. Take it from me, kid. I’ve struggled with a sour gut for years. Never eat a big meal unless you can rest for a bit after.”

“I could have made the run on an empty stomach,” Clay said.

“You never know when you’ll need that strength, and you’ll be all the faster for it. Get out of here,” she said.

“And tell the major to hurry,” she called at the retreating back.

Within twenty-four hours they had the Bears in place at Staging Beta, the final campsite, just a two-hour fast-march from the hotel. Lambert and Major Valentine had worked the contingencies ever since she confirmed that there was some important activity at the hotel in French Lick and set Clay running with his pipe still warm in his pocket.

It would be her job to lead them to Staging Omega, the point where the Bears would make visual contact with the hotel, for the assault.

The column moved well, covering the distance in hard, hour-by-hour hikes with ten-minute rests. Captain Patel’s doing, though he wasn’t on the op—he’d remained in command back at Fort Seng—his march discipline training showed. They ate nuts and dried fruit as they walked, and took water at the rests.

She guided the Wolves, who chose the trail for the rest of the column. She’d had to give one briefing to the Bears. As much as she liked Wolves, the Bears made her uncomfortable. They sounded ready to kill every soul in the hotel, even the laundry staff and the recuperating soldiers. Most fiddled with their blades, guns, and explosives gear while she talked. They looked as though some sorcerer had taken the word “war” and made from it flesh.

She walked down the line, following Valentine a pace behind and just to his left, suppressing the twitchy anxiety the calculating glances from the Bears brought. Savage fighting dogs watching a meat cart pass would show less naked interest.

Supposedly, all Bears wore the same uniform in the form of a combat vest with a patch sewn over the name on the right breast and black knit stocking caps. Only about half wore even one of the items. Most adorned themselves in a mix of bullet-stopping Kevlar panels and Reaper cloth.

They had a flair for atavism that would have brought disciplinary trial in the old U.S. Army. Reaper teeth, finger bones, ears, jewelry taken off those they killed, all sorts of juju hung off their bodies and weapons. Most were scarred and went out of their way to show off the wounds. Strangest of all was their hair. The fighting men of Southern Command were famous for their beards and mustaches, but the Bears took outlandish grooming to new heights of hair control, tattooing, and other body modifications. Sideburns trimmed like scythes, long ponytails dipped in tar, Mohawks, curiously wrought war picks or other oddball hand-to-hand weapons—the display made her think it was a defiant affront to fate itself, as if the Bears were challenging Death to come and take them, and if Death tried, He might just come off the worse from the encounter.

They tended to operate in small groups, and these groups usually modified their uniform in some small manner to match up with one another. A specific style of boot, a headband, a type of feather, trophies taken off dead Reapers… Such atavistic touches added colorful detail to the legend.

Bears growled, quarreled, and shifted from a placid sleepiness to murderous rage—not always at appropriate times in battle. They had a reputation across Southern Command and the United Free Republics as a vicious bunch of brawlers; they were usually garrisoned as far from civilian population as possible, with a few brave souls providing a simulacrum of civilian entertainments outside their bases.

Many of them had up and quit Southern Command, crossed the Mississippi, and followed the numerous supply and communications trails to the newly formed Kentucky freehold. And not a moment too soon. She’d never heard of Oliver Cromwell, but had she been forced to phrase the sentiment of many in Missouri and Arkansas, she would have used something similar to Cromwell’s address to the Rump Parliament: Depart, I say; and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!

The Bears had been trained in reducing lifesign. They didn’t care to do it, usually, preferring to let their presence draw the Reapers within swatting range.

On this operation, however, they had to infiltrate. Getting thirty Bears to the spot in the hills she’d chosen.

The Wolves she could rely on. When the balloon went up, they would cut off road traffic. Nothing but an armored column would get through once they set up their machine guns, light mortars, and grenade launchers covering the road.

She led the Wolves and Bears in a staggered double file down the trail she’d picked out, an old fire road that still seemed to see a little traffic, probably as part of Ordnance training. Just behind her the Bear company commander, a Carolinian who went by the name of Gamecock, walked with his communications tech at his heel like a well-trained dog. The pack radio was functional but silent; the Ordnance might be startled by strange radio traffic picked up by listening posts. Gamecock was well named—he had a swagger to him that his fellow Bears liked. Duvalier thought him the most pleasant of his kind she’d ever known; he was mannered and soft-spoken and moderate in his habits, remarkable enough in a soldier with his combat record, damn near miraculous in a Bear.

Radio silence or no, the Bears would blow it. She’d been on three of these combined raids in her early years as a Cat, and every time a couple of torqued-up Bears ended up attacking enemy posts that had nothing to do with the objective, just to get some fighting in. Two scrubs, and on the third time they went ahead with the attack and were burned. After that she started working Oklahoma and Kansas alone.

Fourth time’s the charm. Maybe.

“What’s that, Miss Duvalier?” Gamecock asked.

Shit, she’d been muttering under her breath again. “About four hours of dark left,” she improvised. “We’re a little ahead. Maybe call a halt here, while we’re still clear of their pickets?”

Gamecock half smiled. “Sure.” He turned to his top sergeant. “Pass the word down the line. We’ll stop just below the notch, there.”

Duvalier gave a coyote yip to signal the wolves ahead and on the flanks, and made a hand gesture for a halt.

Valentine, moving with the middle of the Bear column, came up at the halt to go over her sketched-out map of the hotel and its grounds, and compared it to a couple of photos of French Lick they’d managed to extract from old tourism brochures.

She pulled Val aside after the conference. He was wearing his battle dress of Southern Command uniform and legworm leather. Not anybody’s idea of dashing, and between the scar by his eye and his off-kilter jaw not many would consider him classically handsome. His hair, which she always considered his best asset, was still thick and black, with a few flecks of gray at the temples. She had the urge now and then to run her fingers through it, and a few times he’d even accepted a scalp massage.

Once, he’d been on his way to an important staff position in Southern Command, but a general he’d crossed swords with saw to it that a court-martial wrecked h

im. Even now he was technically only a corporal in the auxiliaries, though everyone under Lambert’s command at Fort Seng called him by his old rank of major.

“I’d no idea you’d moved so many men and gear to Beta. I thought it was just a couple of squads of Wolves.”

“I had a feeling about this one,” Valentine said. “Lambert wanted the Bears out of her hair for a while anyway. They tore up the strip on a rampage.”

Major David Valentine had a sixth sense of some kind. She’d seen it in action too many times not to be a believer. When she’d been looking into him before choosing to train him as a Cat (what seemed like a lifetime ago), his comrades in the Wolves had spoken of a “Valentingle” he’d get when Reapers were around. But it went further than that—he could smell both trouble and opportunity in the wind.

“Let’s hope they can keep it zipped up for another couple hours,” she said.

“Gamecock knows his business. We’ll move fast the last two kilometers. That’ll keep their minds on the West Baden.”

The Wolves took two sets of prisoners as they approached French Lick: about a dozen civilians who lived at a remote roadside who’d heard there was a bunch of new Reapers in the neighborhood and decided to relocate to some relatives’ west of Bloomington, and an Ordnance off-road motorcycle scout training unit that had camped out for the night and hadn’t bothered to set a watch on what they’d considered an overnight joyride. The cycles would make a great addition to the motor pool at Fort Seng, and the soldiers could be put to some useful work in Evansville or Western Kentucky.

Walking the motorcycles, guarding the prisoners and civilians to the point where the civilians could not do much harm even if they told the Kurian Order everything they’d seen and heard, and the usual scouting duties of a column moving in enemy territory meant that a quarter of their Wolves weren’t in communication with the column. Even the least experienced platoon meant a substantial loss of manpower.

“Only take a couple of guys to guard the bunch and the cycles,” Gamecock suggested at the informal council of war at the halt to reorganize.

Dragon Avenger

Dragon Avenger Daughter of the Serpentine

Daughter of the Serpentine Valentine's Resolve

Valentine's Resolve Tale of The Thunderbolt

Tale of The Thunderbolt Valentine's Exile

Valentine's Exile Dragon Rule

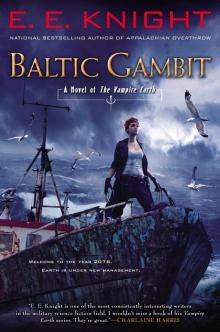

Dragon Rule Baltic Gambit: A Novel of the Vampire Earth

Baltic Gambit: A Novel of the Vampire Earth Lara Croft: Tomb Raider: The Lost Cult

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider: The Lost Cult Dragon Outcast

Dragon Outcast Appalachian Overthrow

Appalachian Overthrow Choice of the Cat

Choice of the Cat Dragon Champion

Dragon Champion Dragon Strike

Dragon Strike Winter Duty

Winter Duty Valentine's Rising

Valentine's Rising Baltic Gambit

Baltic Gambit Dragon Fate: Book Six of The Age of Fire

Dragon Fate: Book Six of The Age of Fire Way Of The Wolf

Way Of The Wolf The Vampire Earth: Fall with Honor

The Vampire Earth: Fall with Honor